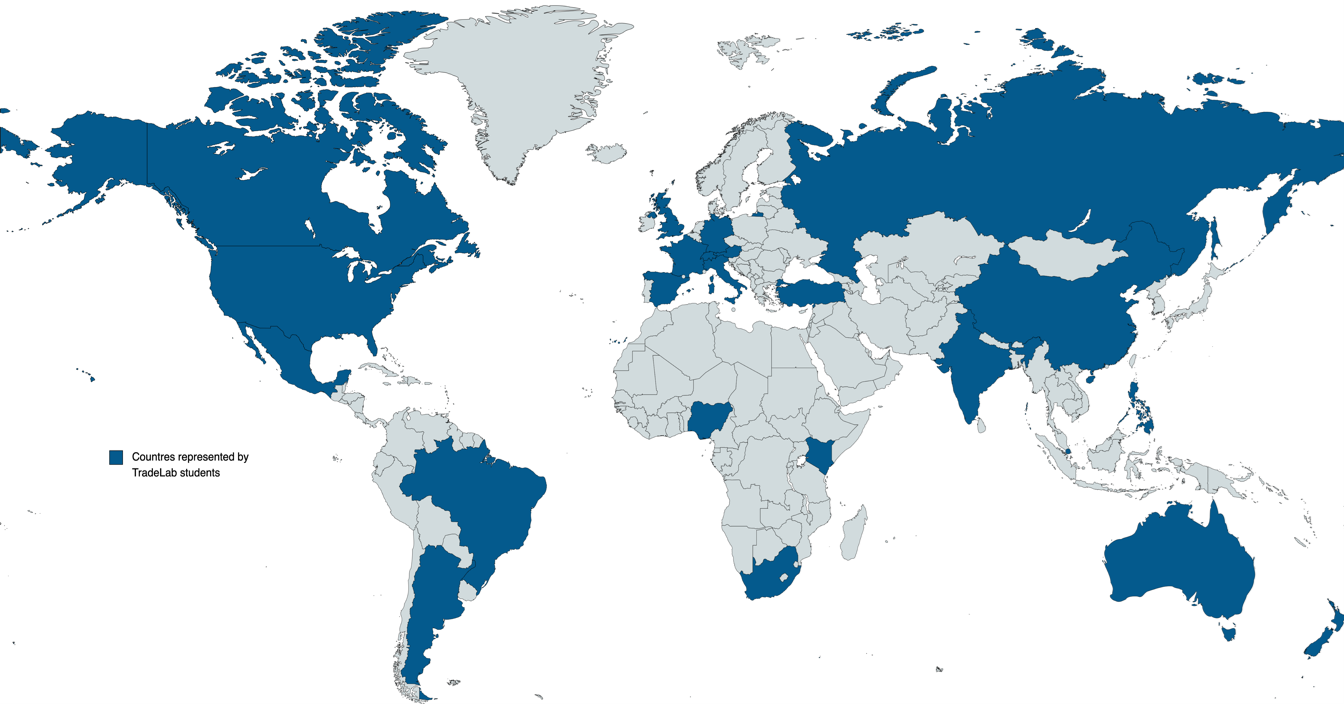

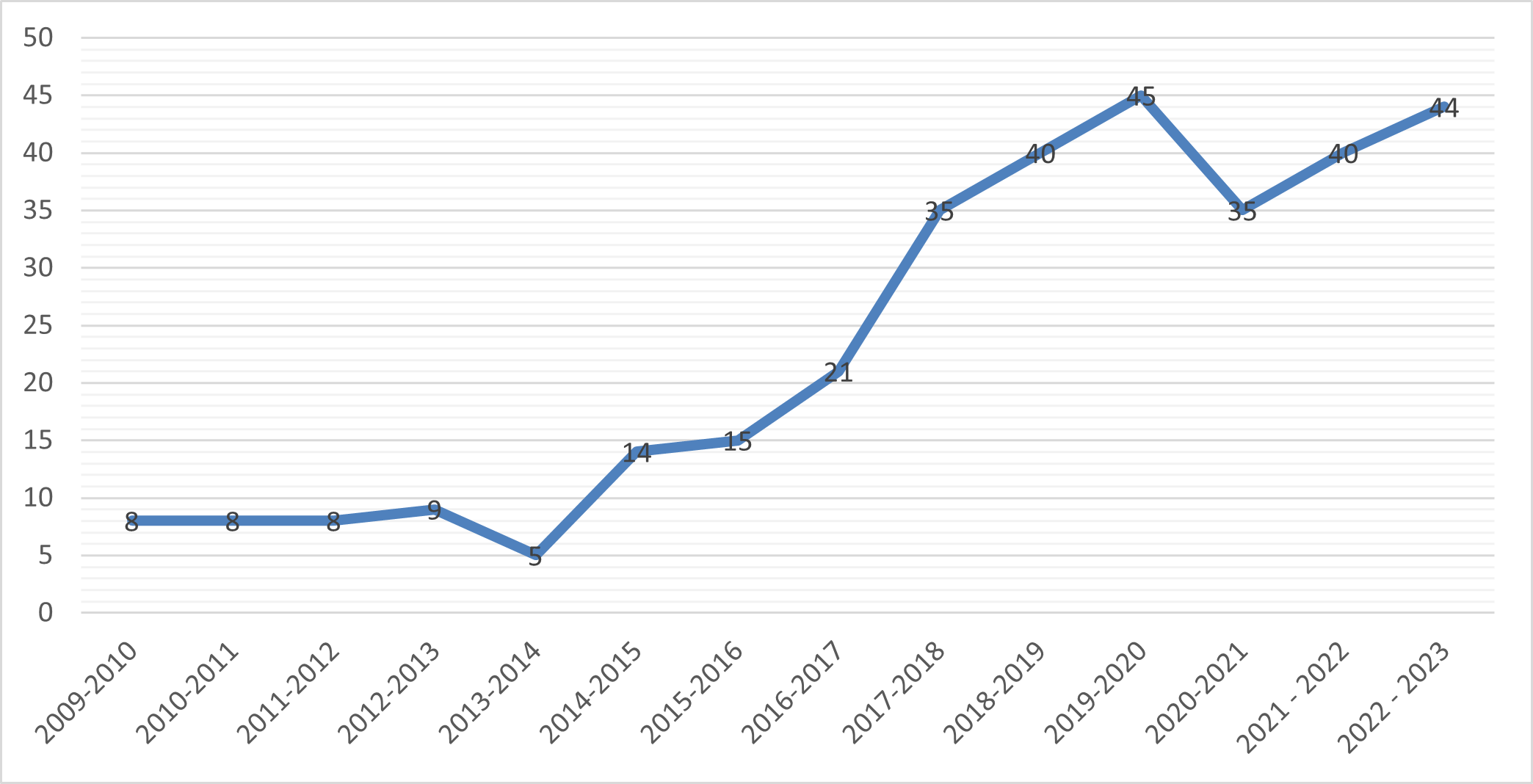

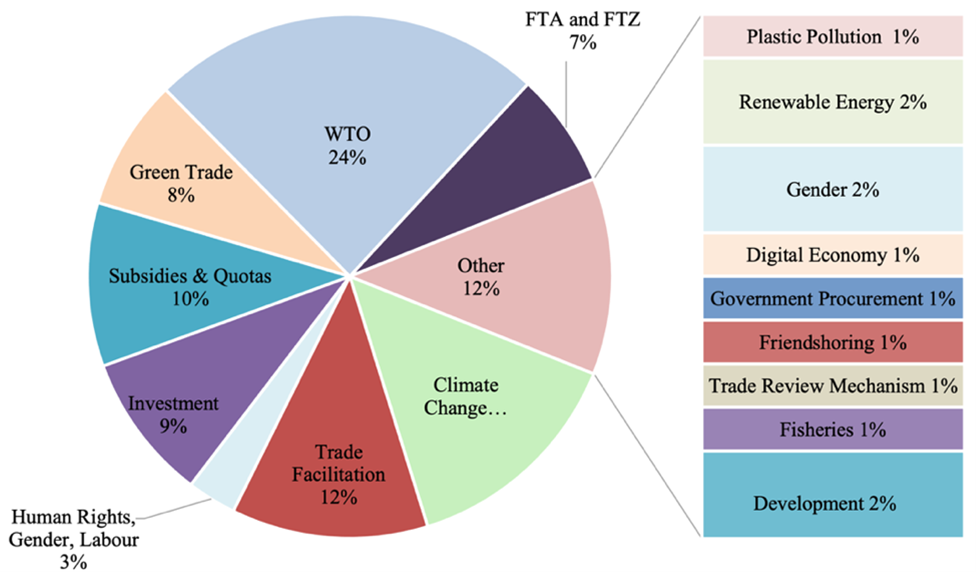

TradeLab is a network of legal clinics and practica that brings together students, academics, and legal practitioners from all over the world to tackle international economic regulatory challenges.

Our Goals:

- To give students a valuable “hands-on” learning experience by addressing real world problems

- To empower beneficiaries—especially smaller stakeholders from developing countries—to reap the full benefits of the global economic regime

- To democratize expertise and promote sustainable economic development